Katy Perry’s $225-million payday began in 1908

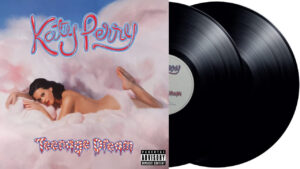

KATY PERRY sold the rights to most of her music for a cool $225 million last month to Litmus Music. It’s the latest in a series of high-profile payouts. Tempted by eye-popping offers from investment firms like Hipgnosis and Shamrock Capital, Paul Simon, Dr. Dre and other artists have sold out — literally.

While the scale of these transactions may be unprecedented, they’ve been a long time coming. These deals are the consummation of a revolution that began over a century ago when music copyright first began its improbable metamorphosis from a limited legal claim to something that can be monetized on a mass scale.

Though the US Congress passed the first copyright laws in 1790, they didn’t extend those protections to musical compositions until 1831.

But the new copyright referred to something very specific: publishing the lyrics and notes as a piece of sheet music.

Anyone who bought a piece of sheet music effectively purchased the right to perform the music, with royalties going back to the composer. But this was a one-time transaction: A single copy of sheet music gave the buyer the right to perform the music an infinite number of times, whether in the comfort of their own home or in front of a paying audience.

This put composers in a bind. In the 1890s, Paul Dresser came out with “On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away,” a sentimental ditty about lost love in Indiana. It sold 500,000 copies of sheet music, earning about $100,000 — one of the most profitable songs of its day. But Dresser never saw a cent from the many performances of his piece.

Nor did he make money off the recordings. The new methods of reproducing musical sounds — the phonograph, which played music from wax cylinders; the gramophone, which relied on discs; and so-called player pianos, which “read” paper rolls — undermined conventional copyright law. They created a situation where, as historian Alex Cummings has written, “nothing was sacred.”

The firms pushing these new technologies argued that, legally speaking, these were performances, not recordings. As such, when a phonograph or player piano company wanted to get the right to produce records or rolls, it simply bought a single copy of sheet music before selling mechanical versions to a mass audience.

Infuriated composers, artists, and performers filed lawsuits against the usurpers, making what now seems like a pretty reasonable claim: mechanical music reproduction wasn’t a performance but a pirated copy. Yet when the Supreme Court heard a key case involving a player piano company in 1908, it ruled against the artists. While a pirated paper copy of a song sheet was still a copyright violation, a gramophone record based on that song was not.

In fairness, the court came to this decision out of deference to the original wording of the 1831 act, which did not anticipate the new technological advancements. Consequently, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes noted in his decision that Congress might want to revise the law to acknowledge that “anything that mechanically reproduces [a] collocation of sounds ought to be held a copy.”

Congress, which passed the Copyright Act of 1909 in response, arguably muddied the waters further. It gave the copyright holder (typically the composer and the music publisher) the right to choose who made the first mechanical reproduction of the work. After that point, though, anyone could record or make copies of the song by paying the copyright holder a compulsory fee of two cents for every copy manufactured.

Members of Congress couldn’t wrap their minds around the idea that a recording of a song deserved protection on par with the underlying lyrics and score. Instead, they tried to frame the problem entirely in terms of the original composer and publisher. This effectively legalized the sale of bootleg copies of recordings.

By the 1960s, the widespread adoption of magnetic tape made large-scale piracy even easier, and when the culprits began issuing illicit copies of albums by artists such as Bob Dylan and the Beatles, it pushed the record companies to take action. They began by lobbying New York State to pass anti-piracy laws that other states quickly emulated.

Though they did not confer copyright, these laws set the stage for Congress to pass the Sound Recordings Act of 1971, which allowed companies to copyright their recordings. A subsequent act passed in 1976 conferred additional protections, giving corporations a 75-year claim to any recordings they created.

In the process, recordings became something that could be bought and sold like any other investment, their value determined by the belief that a popular song will remain so for the foreseeable future. The rise of digital audio files, where the cost of copying and distributing music drops to zero, has made ownership of the copyright — the music and lyrics on the one hand and the recording on the other — an increasingly attractive proposition.

In Katy Perry’s “If You Can Afford Me,” she sings: “Don’t make a bet if you can’t write the check … Cause, I can be bought, but you pay the cost.”

Thanks to the decades-long evolution of musical copyright, investors have concluded this is definitely a bet worth making, no matter how high the cost. — Bloomberg Opinion